Scientists are pioneering a new method to combat snake poison using newly designed protein, which offers hope for more affordable, effective, and accessible antivenom solutions.

This innovative approach, which uses advanced computational techniques and deep-learning, has already shown promising outcomes in neutralizing deadly toxin, potentially transforming the development of antivenom, and offering new approaches for tackling neglected diseases.

Breakthrough Antivenom Research

Researchers have developed new proteins, unlike any found in nature, that can neutralize the most toxic components in snake venom. Researchers have developed these proteins using advanced deep learning and computation methods. These proteins could lead to safer, more affordable and more accessible treatments than existing antivenoms. According to the World Health Organization, each year, more than 2 million people are affected by snakebites. More than 100,000 people die from them, and 300,000 suffer severe complications such as limb deformities and amputations. The most severe snakebites are seen in sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia. Papua New Guinea and Latin America also have a high rate of snakebites. These regions often lack access to effective treatments.

Advancements In Computational Biology (19659007) This groundbreaking computational biology study, aimed at improving antivenom therapies, was conducted by scientists from the UW Medicine Institute for Protein Design, and the Technical University of Denmark. Their findings were published on January 15 in Nature .

Susana Vazquez-Torres is the lead author of this paper. She is from the Department of Biochemistry and the UW Graduate Program of Biological Physics. Her hometown is Queretaro in Mexico, near rattlesnake and viper habitats. Her professional goal is the invention of new drugs to treat neglected diseases and injuries including snakebites.

The Challenge of Elapid Snakebites

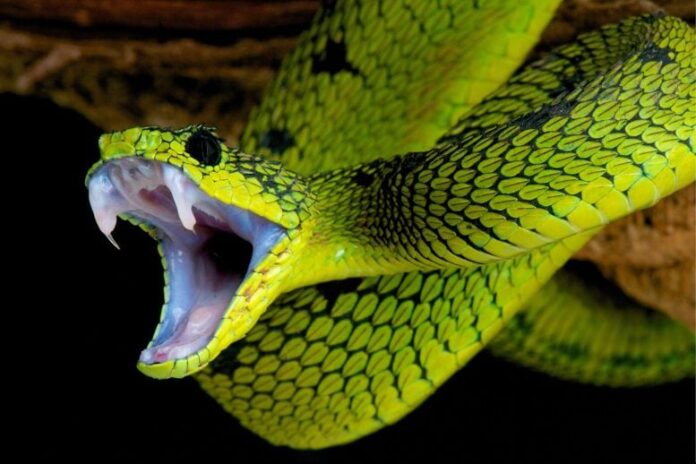

Her research team, which also included international experts in snakebite research, drugs and diagnostics, and tropical medicine from the United Kingdom and Denmark, concentrated their attention on finding ways to neutralize venom gathered from certain elapids. Elapids are a large group of poisonous snakes, among them cobras and mambas, that live in the tropics and subtropics.

Most elapid species

” ” data-gt-translate-attributes=””[{[{“attribute”:”data-cmtooltip”, “format”:”html”}]” ” role=””link”” tabindex=””0″ “> species have two small fangs shaped like shallow needles. During a tenacious bite, the fangs can inject venom from glands at the back of the snake’s jaw. Among the venom’s components are potentially lethal three-finger toxins. These chemicals damage bodily tissues by killing cells. More seriously, by interrupting signals between nerves and muscles, three-finger toxins can cause paralysis and death.

Limitations of Current Treatments

At present, venomous snakebites from elapids are treated with antibodies taken from the plasma

” ” data-gt-translate-attributes=””[{[{“attribute”:”data-cmtooltip”, “format”:”html”}]” ” role=””link”” tabindex=””0″ “> plasma of animals that have been immunized against the snake toxin. Producing the antibodies is costly, and they have limited effectiveness against three-finger toxins. This treatment can also have serious side effects, including causing the patient to go into shock or respiratory distress.

“Efforts to try to develop new drugs have been slow and laborious,” noted Vazquez Torres.

Innovations in Protein Design

The researchers used deep learning computational methods to try to speed the discovery of better treatments. They created new proteins that interfered with the neurotoxic and cell-destroying properties of the three-finger toxin chemicals by binding with them.

Through experimental screening, the scientists obtained designs that generated proteins with thermal stability and high binding affinity. The actual synthesized proteins were almost a complete match at the atomic level with the deep-learning computer design.

In lab dishes, the designed proteins effectively neutralized all three of the subfamilies of three-finger toxins tested. When given to mice, the designed proteins protected the animals from what could have been a lethal neurotoxin exposure.

Promising Results and Future Directions

Designed proteins have key advantages. They could be manufactured with consistent quality through recombinant DNA

” ” data-gt-translate-attributes=””[{[{“attribute”:”data-cmtooltip”, “format”:”html”}]” ” role=””link”” tabindex=””0″ “> DNA technologies instead of by immunizing animals. (Recombinant DNA technologies in this case refer to the lab methods the scientists employed to take a computationally designed blueprint for a new protein and synthesize that protein.)

Also, the new proteins designed against snake toxins are small, compared to antibodies. Their smaller size might allow for greater penetration into tissues to quickly counteract the toxins and reduce damage.

Expanding the Potential of Computational Design

In addition to opening new avenues to develop antivenoms, the researchers think computational design methods could be used to develop other antidotes. Such methods also might be used to discover medications for undertreated illnesses that affect countries with significantly limited scientific research resources.

“Computational design methodology could substantially reduce the costs and resource requirements for development of therapies for neglected tropical diseases,” the researchers noted.

Explore Further: AI Triumphs Over Venom: Revolutionary Snakebite Antidotes Unveiled

Reference: Max D. Overath, Watch-de-de-Torre Hope, Jann Lederger, Andreas H. Laustsen, Kim Boddum, Asim K. Bera, Alex Kang, Iara A. Cardoso, Edward P. P. Crittenden, Rebecca J. Edge, Justin Decarreau, Robert. 15 January 2025, Nature.

Two: 10.1038/S41586-024-08393-X

The senior researchers on the project to design protein treatments for elapid snakebites were Timothy J. Perkins at the Technical University of Denmark and David Baker of the UW Medicine Institute for Protein Design and the Howard Hughes Medical Institute. Baker is a professor of biochemistry at the UW School of Medicine.

The University of Washington

” ” data-gt-translate-attributes=””[{[{“attribute”:”data-cmtooltip”, “format”:”html”}]” ” role=””link”” tabindex=””0″ “> University of Washington has submitted a provisional U.S. patent application for the design and composition of the proteins created in this study.